What is M4A? Your Guide to This Audio Format in Metal Production

Nail The Mix Staff

Ever found yourself staring at an .m4a file someone sent you, or wondering what the hell it actually is when your DAW offers it as an export option? You’re not alone. In the world of metal production, where we’re usually wrestling with massive WAV files for our multi-tracked drums and quad-tracked guitars, M4A can seem a bit out of place. Is it useful? Is it garbage? Will it make your killer snare sound like it’s trapped in a tin can?

Let’s cut through the crap and figure out what M4A is, how it stacks up against other formats you’re already using, and when (or if) you, as a metal producer, should even bother with it.

So, What Exactly IS an M4A File? The Nitty-Gritty

At its core, M4A stands for MPEG-4 Audio. Think of it like a container – a digital box that can hold different types of audio data. Most of the time, when you see an M4A file, the audio inside is compressed using AAC (Advanced Audio Coding).

Here’s the quick rundown:

- It’s a Lossy Format (Usually): AAC, the typical codec in M4A, is a lossy compression format. This means it intelligently throws away some audio information that your ears supposedly won’t miss too much, all to make the file size smaller. This is the same principle behind MP3s.

- Apple’s Baby: M4A got a huge push from Apple. It was the standard format for songs in the iTunes Store and for music loaded onto iPods and iPhones. So, if you’re an Apple user, you’ve been swimming in M4As for years.

- Successor to MP3?: AAC was designed to be more efficient than MP3. Generally, an M4A file using AAC encoding will sound better than an MP3 of the same bitrate, or sound comparable at a lower bitrate (meaning a smaller file).

But here’s a curveball: an M4A container can also hold ALAC (Apple Lossless Audio Codec). As the name suggests, ALAC is lossless, meaning no audio data is discarded. It’s like a ZIP file for your audio, shrinking the size without sacrificing quality. We’ll touch on this distinction more later. For now, just know that when people say “M4A,” they usually mean the lossy AAC version.

M4A vs. The Usual Suspects: How Does It Stack Up for Producers?

Alright, so it’s a compressed audio format. How does it compare to the files you’re already slinging around in your Pro Tools, Logic Pro X, Reaper, or Cubase sessions?

M4A vs. MP3: The Classic Showdown

This is the big one for lossy formats. For years, MP3 was king for sharing and portable listening.

- Quality: At the same bitrate (e.g., 256kbps), AAC (in an M4A) generally offers slightly better audio fidelity than MP3. The differences can be subtle, but AAC often handles transients and high frequencies a bit more gracefully. This means your meticulously crafted cymbal work or the attack of your picked guitar notes might survive the compression slightly better.

- File Size: Because AAC is more efficient, you can often get away with a slightly lower bitrate for an M4A and achieve comparable quality to a higher bitrate MP3, resulting in a smaller file. For example, a 256kbps AAC might sound as good as or better than a 320kbps MP3.

- Compatibility: MP3 still wins on universal compatibility. Pretty much any device or software from the last 20 years can play an MP3. M4A is widely supported, especially on Apple gear and modern devices, but you might hit an occasional snag with older or more obscure players.

- Encoders Matter: The software used to create the MP3 or M4A (the encoder) makes a difference. The LAME encoder is legendary for MP3s, while Apple’s AAC encoder (used in Logic and iTunes/Apple Music) is generally considered top-notch.

The Verdict for Metal Producers: If you need a small, shareable file for quick demos or previews and quality is a concern, M4A (AAC) is often a slightly better choice than MP3, assuming your recipient can play it.

M4A vs. WAV/AIFF: Lossy vs. Lossless (No Contest for Masters!)

This isn’t really a fair fight; it’s more about understanding their different roles.

- WAV/AIFF are Uncompressed (or Losslessly Compressed): These are your workhorse formats for recording, mixing, and mastering. They contain all the original audio data, typically at high resolutions like 24-bit/48kHz or even 96kHz. This is non-negotiable for professional work, and a key reason why understanding what bit depth is so important.

- M4A (AAC) is for Delivery/Convenience: You would never record your screaming vocals or brutal drum kit directly to a lossy M4A. You wouldn’t mix from M4A stems (unless you’re going for some super lo-fi, telephone-mic effect intentionally). And for the love of all that is heavy, do not send M4A files to your mastering engineer or upload them to distributors like DistroKid or TuneCore as your final master. They need WAVs.

- Think of it this way: WAV is the raw, prime steak. M4A (AAC) is a decent jerky – good for a snack on the go, but not what you’re serving for the main course.

The Verdict for Metal Producers: Always, always work with WAV (or AIFF) files for your actual production, mixing, and mastering. M4A (AAC) is purely a downstream format for listening copies or very specific sharing scenarios.

What About ALAC (Apple Lossless Audio Codec) in an M4A?

Remember how M4A is a container? It can also house ALAC.

- Lossless, Like FLAC: ALAC is Apple’s version of FLAC. It compresses file sizes by about 40-60% compared to WAV, but without losing any audio quality. This puts it in a similar category as its non-Apple counterpart, often sparking the FLAC vs WAV discussion for archiving.

- Apple Ecosystem Champ: ALAC is great if you’re heavily invested in the Apple ecosystem (Macs, iPhones, Apple Music) and want high-quality lossless audio that’s a bit smaller than WAV.

- Still Not for Professional Exchange (Usually): While ALAC is lossless, most pro audio workflows still standardize on WAV for interchange between collaborators, studios, and mastering engineers, mainly for universal compatibility and to avoid any potential conversion hiccups.

The Verdict for Metal Producers: ALAC-in-M4A can be a good option for personal archiving of your mixes in high quality if you use Apple devices, but WAV remains the king for professional handoffs.

When Should Metal Producers Actually Use M4A Files?

So, given all this, when does M4A (specifically the common AAC version) actually make sense in a metal producer’s workflow?

Sending Demos and Pre-Production Ideas

Got a sick new riff idea you tracked quickly in GarageBand on your iPad, or a rough mix of a song you want to send to your bandmates? M4A is your friend here.

- Smaller Files: Way smaller than sending a full WAV, making it easier to email or chuck into a Dropbox, Google Drive, or WeTransfer link.

- Good Enough Quality: For sketching out ideas or getting feedback on song structure, the quality of a well-encoded M4A (say, 256kbps AAC) is perfectly fine. No one’s critiquing the high-end air of your hi-hats on a pre-pro demo.

Client Previews (with caveats)

Sometimes a client just wants a quick listen on their phone or laptop.

- Convenience: An M4A is easy for them to play on an iPhone or Mac without fuss.

- Warning! Make it clear this is not the final quality for critical listening or sign-off. Always follow up with high-quality WAVs for actual approvals, especially before mastering. You don’t want them making mix revision notes based on artifacts from a lossy codec.

Personal Listening and Reference Tracks

Loading up your phone or portable music player with your latest mix revisions or some commercial reference tracks?

- Space Saver: M4As (or MP3s) save space compared to carrying around WAVs of everything.

- Reference Wisely: If you’re A/B-ing your mix against commercial tracks, try to use high-quality sources. Many streaming services now use AAC (like Apple Music or YouTube Music at higher settings), so an M4A you make might be fairly comparable to what you hear there.

What Not To Do: The Cardinal Sins of M4A

Just to hammer it home, avoid these like a poorly tuned floor tom:

- NEVER send M4As to a mastering engineer. This is a critical rule in the mixing vs. mastering workflow; they need your full-resolution WAV (e.g., 24-bit/48kHz, with headroom).

- NEVER use M4As as source material for serious mixing. Garbage in, garbage out. The only exception is if you’re deliberately using a low-quality file for a specific creative effect, like an intro or a breakdown.

- NEVER upload M4As as your final master to digital distributors. They almost universally require WAV files.

Creating and Working With M4A Files in Your DAW

Okay, you’ve decided M4A is right for a specific task. How do you make one?

Exporting M4A from Popular DAWs

Most modern DAWs can export directly to M4A (AAC) or have straightforward workarounds.

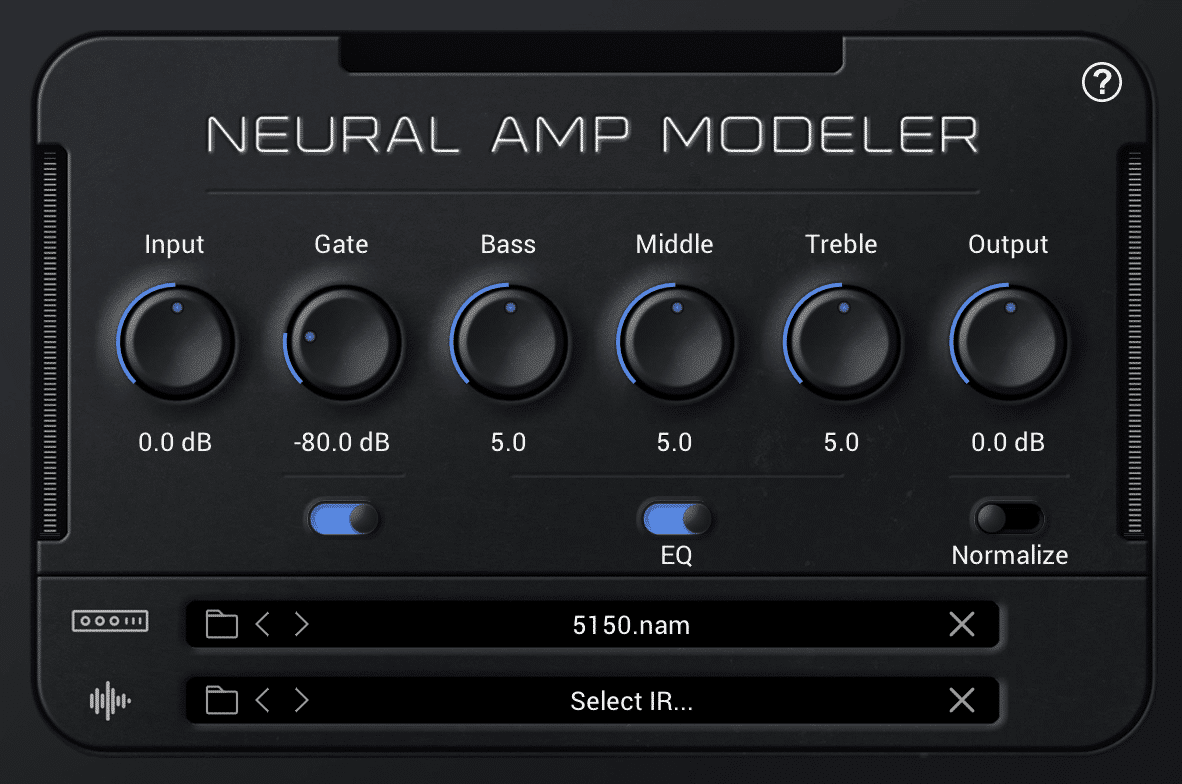

- Logic Pro X: Has native AAC export. When you bounce (Cmd+B), you can select M4A (ACC) as a destination. You’ll usually get options for bitrate like 128kbps, 256kbps, or even variable bitrate (VBR). For good quality demos, aim for 256kbps AAC or higher.

- Pro Tools: You can “Bounce to QuickTime” and then choose M4A/AAC from the format options there. Or, more commonly, bounce a high-quality WAV and then convert it.

- Reaper: You might need to install the FFMPEG libraries to enable direct AAC export. Go to Options > Preferences > Media > Video/Import/Misc and it’ll usually show you where to download and place them. Otherwise, export WAV and convert.

- Cubase/Nuendo: Similar export options in the “Export Audio Mixdown” dialog, allowing you to choose MPEG-4 Audio.

- Settings to Watch:

- Bitrate: For AAC, 192kbps is okay for quick shares, 256kbps is a good sweet spot for quality vs. size, and 320kbps is excellent for lossy.

- Sample Rate: Usually, you’ll want this to match your session (e.g., 44.1kHz or 48kHz). The M4A encoder will handle it.

- Dithering: If you’re exporting from a 24-bit session to a 16-bit equivalent for the M4A (which is typical for lossy formats), make sure dithering is applied once at the very end of your mastering chain or by the export process if it’s changing bit depth. Many DAWs handle this automatically when exporting to lossy formats, but it’s vital to understand what is dithering to prevent unwanted artifacts.

Conversion Tools: When Your DAW Falls Short or for Batch Jobs

If your DAW is clunky with M4A, or you have a pile of WAVs to convert:

- iTunes/Apple Music (on Mac/PC): Still a surprisingly decent and free converter. Go to Music > Preferences > Files > Import Settings, choose “AAC Encoder” and your desired quality (e.g., “High Quality 256kbps”). Then you can right-click songs in your library and choose “Create AAC Version.”

- Audacity (Free, Cross-Platform): With the FFMPEG library installed, Audacity can import WAVs and export to M4A (AAC).

- Dedicated Converters (Paid): Tools like dBpoweramp (Windows) or XLD (Mac) are fantastic for high-quality, batch audio conversion to a huge range of formats, including M4A with fine-grained control over AAC encoder settings.

Optimizing Your Mix BEFORE You Even Think About M4A

Here’s the real kicker: no audio format is going to save a shitty mix. In fact, lossy codecs like AAC can often exacerbate problems in your mix. That pristine, punchy mix you hear in your studio on your Adam A7Xs or through your trusty Sennheiser HD650s can turn into a smudged, artifact-ridden mess after it’s squeezed through a lossy encoder if you’re not careful.

Nailing the Low End and Highs for Codec Survival

Lossy codecs can get weird with extreme frequencies and complex transients.

- Tight Low End: Muddy bass or an out-of-control sub-low kick drum will just turn into distorted mush after AAC encoding. Make sure your low end is tight, focused, and not overly resonant. This isn’t just about scooping with your FabFilter Pro-Q 3; it’s about balance and control.

- Tame the Fizz and Sibilance: Harsh cymbals, overly bright distorted guitars that sound like a swarm of bees, or piercing “S” sounds on vocals can become even more grating after encoding. Learning to identify and tame sibilance is a crucial mixing skill. Getting your EQ right is crucial before any export. If your guitars are fizzing out or your kick drum is pure mud, no M4A is gonna save it. Dive deeper into how to EQ metal guitar to make sure your core tones are solid.

100+ Insanely Detailed Mixing Tutorials

We leave absolutely nothing out, showing you every single step

Headroom and Dynamics: Don’t Squash It To Death Pre-Codec

Slamming your mix into a brickwall limiter like a Waves L2 or FabFilter Pro-L 2 might sound loud, but it can create problems for lossy encoders.

- Leave Some Headroom: When exporting the WAV that you might later convert to M4A (or if your DAW creates the M4A from your mix bus directly), don’t print it at 0dBFS. Leave at least -1dBTP (True Peak) headroom. Many codecs can introduce slight level increases, leading to clipping if your master is already at the digital ceiling.

- Over-Compression is a Killer: Highly compressed or limited material gives the encoder less to “work with” in terms of psychoacoustic optimization. This can lead to more audible artifacts. Smart compression can make your mix punchy and controlled, but overdo it and the M4A encoder will have a field day making it sound worse. First, you need to understand what a compressor does to get that balance.

Checking Your Mix (Always!)

Before you even think about formats, check your mix:

- In Mono: Collapsing your mix to mono on something like a single Auratone MixCube or even just a mono utility plugin on your master bus will instantly reveal phase issues and balance problems.

- On Different Systems: Listen on your main studio monitors (e.g., Yamaha HS8s, Barefoot Footprint01s), on headphones (Audio-Technica ATH-M50x are a studio staple for a reason), in your car, on a laptop, on earbuds. What sounds killer in one spot might fall apart elsewhere.

If you want to see exactly how pro mixers get their tracks sounding massive and dealing with these exact issues before they even think about exporting to M4A or anything else, that’s where Nail The Mix comes in. Imagine watching guys like Will Putney, Jens Bogren, or Dan Lancaster build a mix from the raw multitracks, explaining every EQ move on those brutal guitars, every compression tweak on the drums… you get it all. Learn more about how to mix modern metal like a pro and see how it’s done.

The Bottom Line: M4A in a Metal Producer’s Toolkit

So, what’s the final word on M4A for metalheads making music?

- It’s a Tool, Not a Religion: M4A (usually AAC) is a perfectly decent lossy audio format that offers good quality for its file size, especially within the Apple ecosystem.

- Know Its Place: It’s great for demos, quick shares, personal listening, and client previews (with clear communication). It is not for professional mastering, archiving your final mixes (unless it’s ALAC for personal use), or delivering masters to distribution. WAV is your undisputed champion for those critical tasks.

- Quality In, Quality Out: The best M4A in the world won’t fix a bad mix. Focus on getting your source audio sounding incredible with solid recording, editing, and mixing techniques.

Don’t fear the M4A. Understand it, use it wisely for the right tasks, and get back to crafting those face-melting metal anthems.

Get a new set of multi-tracks every month from a world-class artist, a livestream with the producer who mixed it, 100+ tutorials, our exclusive plugins and more

Get Started for $1